Building a network of freshwater monitoring experts

Photo credits: Kali Brauckmann, Emma Griggs, Julian Heavyside

Communities across B.C. are leading efforts to improve monitoring of freshwater habitats – essential for Pacific salmon across their life cycle – by tracking stream temperatures and identifying cool zones for salmon. Innovative solutions to identify and count salmon, including the use of artificial intelligence, are also being deployed to provide in-season updates on salmon returns. Gathering this kind of baseline data has been a historic challenge due to fragmented efforts and limited resources. By expanding local monitoring capacity, these new approaches are helping close critical knowledge gaps and guide effective fisheries management and watershed conservation.

In February, the Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) and the Snuneymuxw First Nation co-hosted a workshop gathering over 50 partners from across B.C. to create a stronger network for scaling up freshwater monitoring efforts.

“This workshop was a great opportunity to learn from other communities that are doing similar work, so we can move forward and create better conservation and restoration plans,” says Kali Brauckmann, Project Lead, Snuneymuxw Marine Division.

Thanks to the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund, PSF has collaborated with 35 communities since 2023 to enhance monitoring efforts that support climate-resilient salmon ecosystems. Funds have helped acquire equipment, refine best practices, and design new monitoring programs for partners across B.C. to fill gaps.

Pacific salmon can travel 50 kilometres per day on their upstream migration. But with climate change comes warming temperatures, and many B.C. streams now exceed 20°C in the summer, making these migrations even more grueling – and life-threatening – for salmon.

Natural cold zones in streams, or thermal refuges, can help salmon survive increasingly high stream temperatures. PSF is working with local First Nations and BCIT’s Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems Hub to help identify and protect these salmon ‘cooling centres’ with drones.

“Finding thermal refuges with the drone mapping is so important. Once we know where they are, we can work on creating deeper pools around those areas where cold groundwater flows up, which gives salmon an escape from shallow, warmer waters,” says Brauckmann.

For the Snuneymuxw Marine Division, this work is part of a larger mission to rebuild the Nanaimo River for spring and summer Chinook. Once thermal refuges have been mapped, they can prioritize riparian replanting and stream reconstruction efforts to protect these cool spots. Additional drone surveys will help the team track the impact of their restoration efforts over time.

While identifying thermal refuges helps salmon survive in the short term, understanding the broader trends of stream temperature changes is equally critical. Climate change and watershed degradation are reshaping salmon habitats, and without long-term data, it’s challenging to develop targeted conservation measures.

To close this gap, PSF is working with partners across B.C. to expand community-led freshwater temperature monitoring – providing equipment, training, and technical expertise to help local groups collect high-quality, standardized data.

PSF is also crowdsourcing freshwater temperature data to create centralized, open-access resources. Data from more than 1,500 monitoring sites is now being processed and loaded onto the Pacific Salmon Explorer, the most comprehensive salmon data platform in B.C. To date, a growing network of 40 organizations – including First Nations, government agencies, and streamkeeper groups – have contributed data. By making critical information accessible, these tools empower communities to take faster, more effective action for salmon.

For remote communities with limited resources, where salmon streams are often only accessible by boat or aircraft, monitoring can be exceptionally difficult.

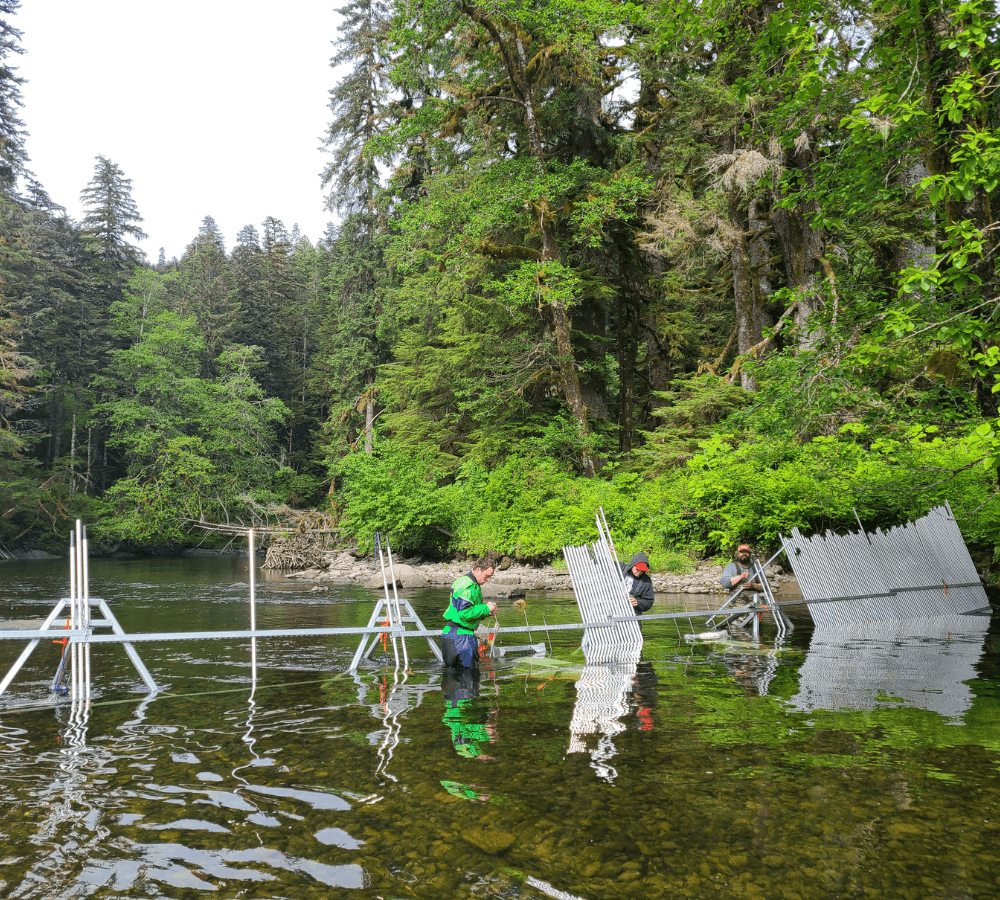

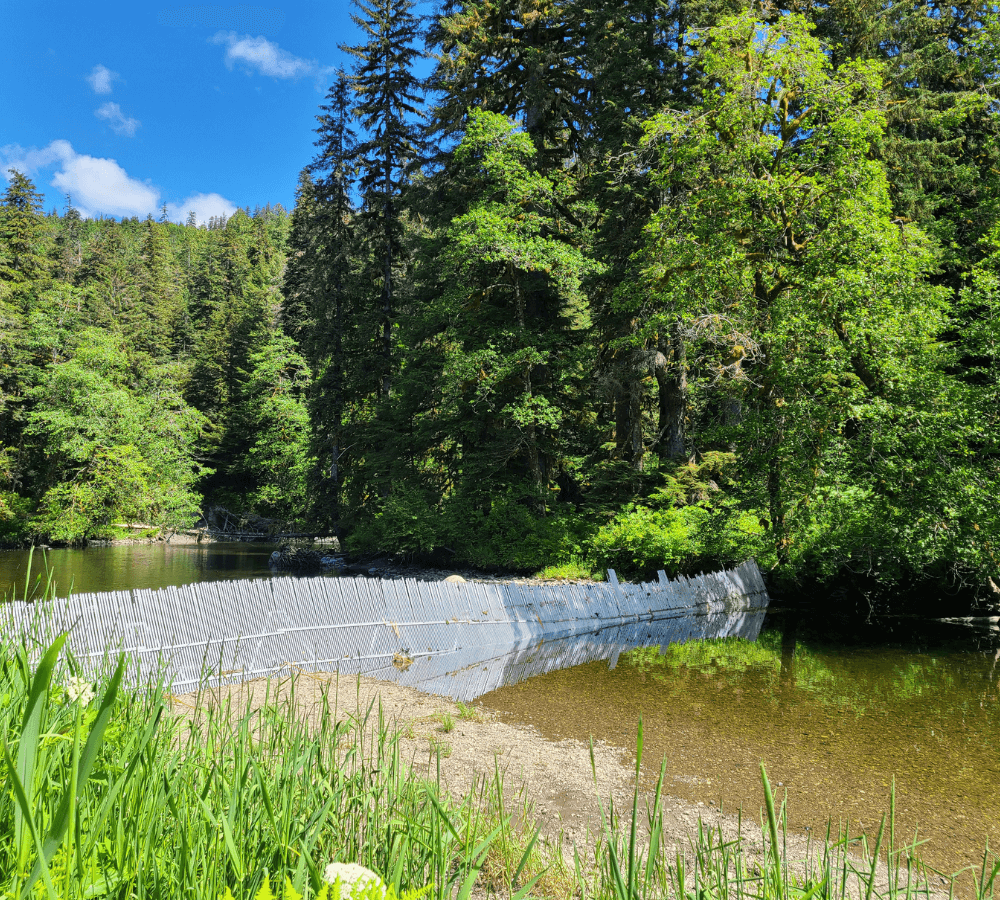

PSF is collaborating with the Wild Salmon Center, Simon Fraser University (SFU), Lumax Ecologial Analytics, and nine First Nations partners to use artificial intelligence (AI) tools for salmon counting and identification. Since 2020, weirs — traditional First Nations fences used to manage salmon — have been paired with AI-powered computer vision models and cameras to automate monitoring efforts.

The Gitga’at Nation, whose territory spans a vast area surrounding Hartley Bay on the North Coast, is using this technology to gain valuable insights into local salmon.

“We wanted to launch and manage our own initiative to develop a reliable dataset on salmon returns, so that we can advocate for more sustainable fisheries management,” says Martin Ostrega, Fisheries Manager, Gitga’at First Nation’s Oceans and Lands Department.

With support from the community, Ostrega oversaw the installation of a new weir in a culturally important site.

“Having this AI technology installed at the weir is a great tool for improving our understanding of local salmon populations and ensuring the Nation has ownership and direct access to important fisheries data,” adds Ostrega.

This year, SFU’s computer science team retrained the computer vision models, achieving an accuracy rate exceeding 90 per cent. The goal is to deliver in-season data to First Nations on a weekly basis, supporting rapid and informed decision-making for local experts like Ostrega.

As climate change continues to affect salmon habitats, community-led solutions are more important than ever. Through these efforts, PSF is building capacity for data-driven, coordinated action to protect salmon and their freshwater ecosystems.

What makes a salmon survivor?

What makes a salmon survivor?