Photo credits: Peter Mather, Manu Keggenhoff

Pacific salmon are mostly declining in northwest B.C. and the Yukon, yet there is a silver lining. Varied status outcomes offer hope that some salmon, at least, are doing well. A report from the Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) has provided a more in-depth look at salmon biodiversity in the Northern Transboundary region, with new data and status assessments released in the Pacific Salmon Explorer. However, major data gaps limited the analysis.

This vast, remote region includes six river basins – the Alsek, Chilkat, Taku, Whiting, Stikine, and Unuk – that straddle the border between Canada and the United States. Salmon that spawn in Canada migrate to and from the ocean in southeast Alaska, and international agreements like the Pacific Salmon Treaty guide salmon management in the region.

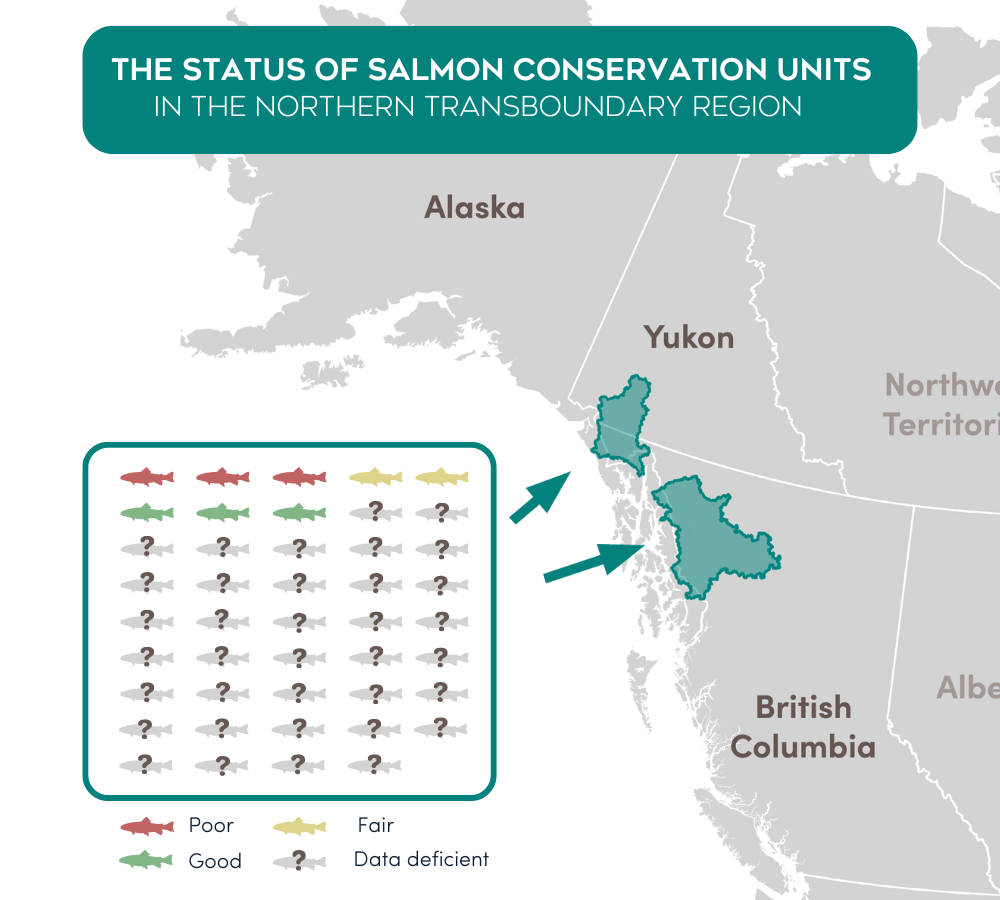

PSF examined 44 distinct groups of salmon and steelhead, known as Conservation Units (CUs), in the Northern Transboundary region. Given the limited focus of monitoring efforts, PSF could not assess the biological status of 82 per cent of CUs (36 of 44), leaving the status of all coho, pink, chum, and steelhead CUs unknown. Without data at the appropriate scale, CUs may be at risk of undocumented extinctions.

“Maintaining resilient salmon in this region depends on being able to assess and manage salmon at the level of Conservation Units,” says Stephanie Peacock, Senior Analyst, PSF.

“Monitoring and conserving healthy, diverse salmon populations stabilizes abundance at the regional scale – just like a diverse investment portfolio stabilizes returns.”

What are Conservation Units?

Conservation Units (CUs) are groups of wild Pacific salmon identified for conservation based on unique biological, genetic, or ecological traits. Salmon evolved these distinct qualities – like body size or spawn timing – to adapt to the specific habitat conditions they face.

Out of the eight CUs that PSF could assess, one was Alsek Chinook, which are struggling. The remaining seven were lake-type sockeye, and the status outcomes were split between ‘poor’, ‘fair’, and ‘good’. Even lake-type sockeye CUs within the same river basin are experiencing different conditions, or responding differently to shared pressures. This hint of diversity in salmon responses provides hope that salmon in the region have maintained their resilience.

PSF’s freshwater habitat assessments revealed a low overall threat of degradation in the region. In certain watersheds, wildfires and mining posed high threats to salmon habitats, with both of these pressures expected to intensify in coming decades.

For example, the 2018 wildfires in northern B.C. disturbed all spawning habitat for Stikine Summer steelhead and significant areas of habitat for Tahltan lake-type sockeye (34 per cent) and Stikine-Early Timing Chinook (15 per cent). Increased wildfire activity can escalate negative impacts to salmon by increasing sedimentation in streams, landslides, vegetation loss, and habitat degradation.

The region also has 120 past and current mines, with the potential for increased mining exploration as glaciers recede and expose untapped mineral deposits. Mining can harm salmon by releasing toxic chemicals, burying streams, and changing water flow — effects already observed in the region. Environmental disasters, like the abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine that caused ongoing acid mine drainage into salmon habitat in the Taku River basin, are a reminder of the potentially severe impacts of mine developments.

Keeping up with climate change

In northern river basins, climate change is causing temperatures to increase three times faster than the Canadian average, leading to warmer waters, reduced flows, and landslides that disrupt salmon habitats. However, the large glaciers and relatively cool climate of the Northern Transboundary Region make it a potential salmon stronghold – if salmon are given an opportunity to adapt.

“Existing monitoring and management systems were designed when there was less emphasis on monitoring and conserving salmon biodiversity,” says Katrina Connors, Senior Director, PSF.

“These systems need to evolve to better protect the diverse habitats in these river basins – and the diverse salmon populations they support.”

For instance, current monitoring efforts in the region focus on major stocks supporting commercial fisheries, with limited data collected for salmon outside of the three major river basins (Alsek, Taku, and Stikine). In the report, PSF recommends enhancing data availability and quality at the scale of CUs to better assess the biodiversity within – and beyond – commercial stocks in the region.

One strategy to address this is to increase support for Indigenous communities to monitor and manage salmon and freshwater habitats in their territories, which can be strengthened with tools such as automated monitoring technologies, rapid responses to climate emergencies, or ecosystem-based salmon recovery plans.

The transboundary nature of this region also presents significant challenges for salmon conservation, requiring international cooperation for sustainable management.

“With the American and Canadian governments entering a renegotiation period for the Pacific Salmon Treaty, there is an opportunity to design monitoring and management systems to better assess and conserve salmon biodiversity,” says Connors.

Learn more in ‘The Status of Pacific Salmon & Their Habitats in the Northern Transboundary Region’ snapshot report.

Learn more in ‘The Status of Pacific Salmon & Their Habitats in the Northern Transboundary Region’ snapshot report.

The Pacific Salmon Explorer is the most comprehensive source of data on salmon and steelhead in British Columbia. PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program has been collaborating with First Nations, Crown governments, academics, non-profits, and independent experts for more than a decade to share the best available data for Pacific salmon in B.C. and the Yukon.