Artificial intelligence to monitor wild salmon

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 edition of Salmon Steward, the Pacific Salmon Foundation’s quarterly print magazine.

British Columbia’s extensive coastline, numerous salmon-bearing rivers, and remote wilderness areas create significant challenges for monitoring salmon populations. This is particularly true on British Columbia’s North and Central Coast where many salmon streams are only accessible by boat or aircraft.

However, the importance of monitoring the health and abundance of Pacific salmon has never been more urgent. The rapid pace of climate change is challenging the ability of Pacific salmon to adapt to an increasingly unpredictable environment. Monitoring the returns of adult salmon is essential for understanding the status of salmon populations and informing conservation and management actions. This is currently hindered by a lack of timely information on returning adult salmon.

Artificial intelligence (AI) provides a novel and cost-effective solution. By building AI tools that leverage computer vision models, PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program in collaboration with the Wild Salmon Center is partnering with First Nations to address the critical challenge of monitoring wild salmon and collecting in-season data in remote salmon-bearing watersheds.

Since 2020, PSF and the Wild Salmon Center have been working with Simon Fraser University, and the Heiltsuk, Haida, and Kitasoo Xai’xais First Nations, as well as the Gitanyow Fishery Authority and the Skeena Fisheries Commission to develop computer-vision models for automating the identification and real-time counting of salmon using videos and sonar cameras.

A technician reviews Yakoun River computer vision images (Leah Honka).

First Nations-led stewardship

Christina Service, a biologist with Kitasoo Xai’xais Stewardship Authority (KXSA), supports the design and operation of the Kwakwa River weir — a fence (or weir) installed across a salmon-bearing stream to help count (in this case using autonomous counting via AI) the number of adult spawners that are passing through.

She notes that the Kwakwa is not classified as a high-value river because the salmon that spawn there do not support any major commercial fisheries. As such, DFO does not monitor returns of local populations, and the AI technology is very helpful for resourcing a monitoring program that would otherwise not be funded.

“The reality is, the Kitasoo Xai’xais are a nation of 350 to 400 people in a very large area. We simply couldn’t get this scale of information on important indicator stocks without the AI tool,” says Service. “We get really high resolution, high-quality data that doesn’t exhaust our local capacity.”

William Housty, conservation manager with the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, uses the technology to automate in-season video counting at the Koeye River weir.

“Heiltsuk has always had a vested interest in their territory and sustainably managing the resources within it. Sockeye has always been a targeted species for food, social, and ceremonial purposes, and Koeye has always been a top producer of sockeye for the community,” he says.

Sockeye salmon in the Kwakusdis River, Heiltsuk territory. (Olivia Leigh Nowak)

He notes that despite the importance of sockeye, Heiltsuk and DFO previously had little information on the Koeye sockeye numbers. The lack of data prompted questions around the overall health of the local population and what a sustainable harvest to ensure that the sockeye population stays stable is.

“Answering these questions was beyond our capacity, so we developed this partnership to start to answer some of them,” says Housty.

“These tools have helped create more certainty with respect to harvesting sockeye from the system, and more confidence in the management practices that we have in play.”

Traditional knowledge braided with computer vision

From the project’s onset, the Salmon Watersheds team connected with Dr. Will Atlas, a post-doctoral fellow at UVic at the time.

Atlas says an interesting element of the AI monitoring is the incorporation of weirs, a traditional First Nations method for salmon management used for thousands of years before colonialism. He notes that weirs were banned by the original Canadian Fisheries Act in order to protect the financial interests of canneries.

“Braiding the ancient technology of weirs with computer vision allows for self-determination. Now First Nations hold the data to inform decision-making in-season and out,” says Atlas.

He notes that the technology enables cost-effective data collection in places that were previously inaccessible.

“The truth of the matter is, you can’t hire enough people to do the work that four hours of data will validate,” he says. “Computer vision is a very powerful tool. It is time to build AI to empower local people — those in remote and Indigenous communities — for decision-making and co-governance.”

Outcomes

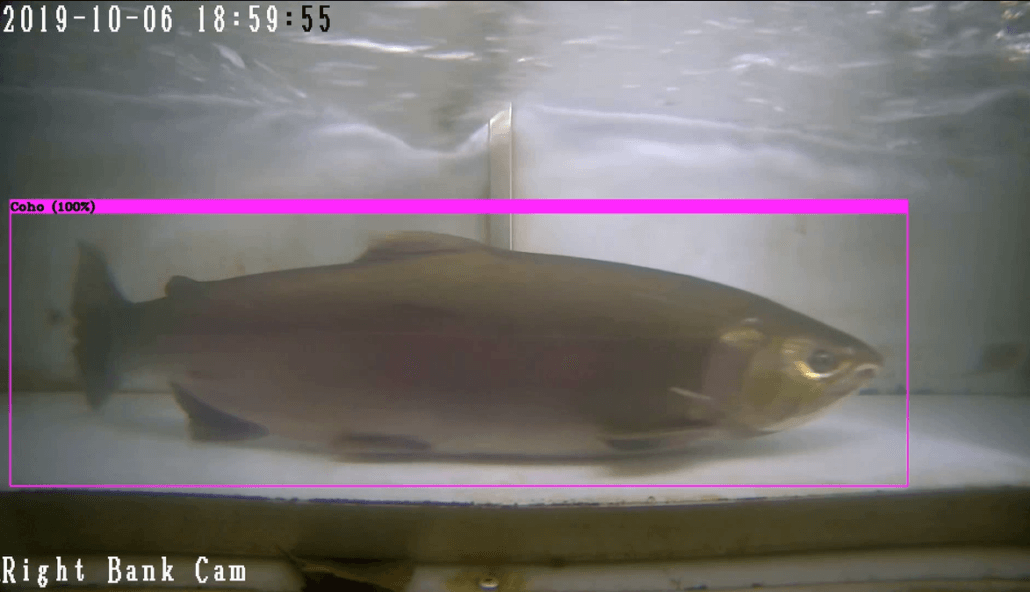

During the initial pilot project, funded by the BC Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund (BCSRIF), the team collected and labelled 530,000 images, developed and trained a computer-vision model which achieved 90 per cent accuracy for automated counts of coho and similarly high performance for sockeye, creating an open-source software for identifying and counting salmon. They are also developing a transferable package of tools and instructions that enable the widespread use of automated video monitoring technology.

A coho salmon swims through a counting fence and is tracked by the computer-vision model.

A research paper ‘Indigenous Systems of Management for Culturally and Ecologically Resilient Pacific Salmon’ published in BioScience (February 2021) was another important outcome that highlights the importance of traditional First Nations technologies for monitoring.

With the success of the pilot project, the team plans to expand work with 12 First Nations and develop an app for users to train models for their watersheds. Additionally, PSF’s Community Salmon Program recently granted funding to Gitanyow, Heiltsuk, and Kitasoo First Nations to advance work on autonomous weirs with video counting technology.

How it works

- Computer-vision models are developed by scientists to enable rapid, automated detection, tracking, and identification of objects.

- Thousands of frames of pre-labelled images or videos are used to ‘train’ the model, teaching it what to look for.

- As the amount of training data increases, the model learns and becomes increasingly reliable at identifying objects.

- Once the model has been trained and tested and its accuracy is confirmed, the model can be used to automate counting salmon, a task that is especially valuable in remote sites.

Special thanks to the RBC Foundation’s Tech for Nature program, which recently provided $200,000 to expand this project.

The BC Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund is funded by the Government of Canada and the Province of British Columbia.