Invasive Species Alert

Prolific across the Pacific Northwest, invasive European green crabs threaten salmon habitat. Early detection and monitoring efforts can help minimize their spread.

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 edition of Salmon Steward, the Pacific Salmon Foundation’s quarterly print magazine.

Native to Europe and North Africa, the European green crab (EGC) first arrived in British Columbia in 1998. European green crabs are considered one of the 10 most unwanted invasive species by DFO due to their ability to tolerate a wide range of temperatures and salinities and outcompete native crabs. They disrupt estuarine and marine ecosystems in a variety of ways. Burrowing into eelgrass beds, they destabilize vital habitat, devastating juvenile salmon dependent on these meadows.

“I have seen more than 10,000 green crabs pulled out of Cypre River estuary in Ahousaht territory, critical juvenile salmon habitat, in one day,” says Crysta Stubbs, science department director with Coastal Restoration Society.

The EGC likely spread to North and South America, Japan, South Africa, and Australia in the ballast of ships. These non-native crabs can rapidly colonize new grounds as they drift further in warming ocean currents. (Maria Catanzaro)

Juvenile salmon and forage fish use eelgrass meadows as habitat to attract their preferred food and find refuge from predators. However, early-detection monitoring and mass trappings are solutions to prevent EGC takeover. PSF, Coastal Restoration Society (CRS), and First Nations communities are collaborating to identify EGCs and safeguard critical salmon habitat.

“I have seen more than 10,000 green crabs pulled out of Cypre River estuary in Ahousaht territory, critical juvenile salmon habitat, in one day using only 40 traps. The most startling part is that there was virtually no bycatch, demonstrating just how intensely overrun these critical nearshore habitats are with EGC and emphasizing the need for widespread control and management efforts as soon as possible,” says Crysta Stubbs, science department director with CRS.

Kyla Sheehan (PSF) and Christine Spice (DFO) at an EGC training session. (Maria Catanzaro)

“When European green crabs are trying to invade a new place, they are typically higher up in the intertidal in lagoons, side channels or small standing pools, and are often found in a muddy substrate near freshwater influence,” says Maria Catanzaro, a PSF biologist.

Without intervention, the EGC harbours the potential to weaken fisheries for shellfish, bivalves, and salmon. But before populations establish, there are clues to find them.

“When European green crabs are trying to invade a new place, they are typically higher up in the intertidal in lagoons, side channels or small standing pools, and are often found in a muddy substrate near freshwater influence. They want cover and food. If you see vegetation in or near the water, sculpins, and native shore crabs, that is a space they would typically be found in first. If they are able to establish, they often move to deeper areas and could potentially disrupt eelgrass beds,” says Maria Catanzaro, a PSF biologist.

Early detection monitoring remains paramount in stopping EGC from establishing populations. The team identifies sites to monitor for EGC using a PSF geospatial tool that points researchers to the most likely habitats they may invade first.

From there, the Early Detection Monitoring Team from PSF and CRS, along with community members, scout areas of interest, placing traps and looking for indications of EGCs. Sites are continually checked monthly from April to September. If EGCs are detected, the next steps are to determine the level of capacity of PSF, CRS, communities, or DFO to conduct more frequent trapping work to try to eliminate them.

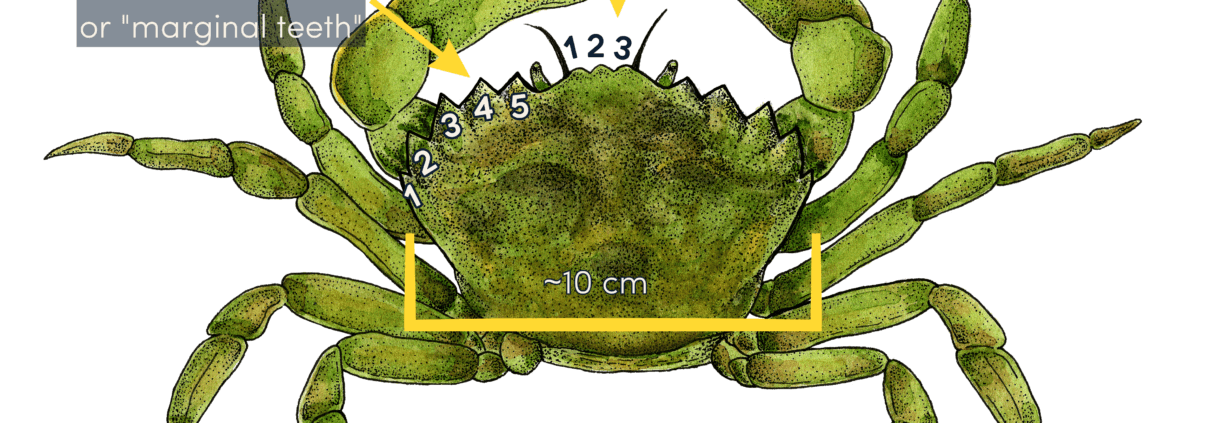

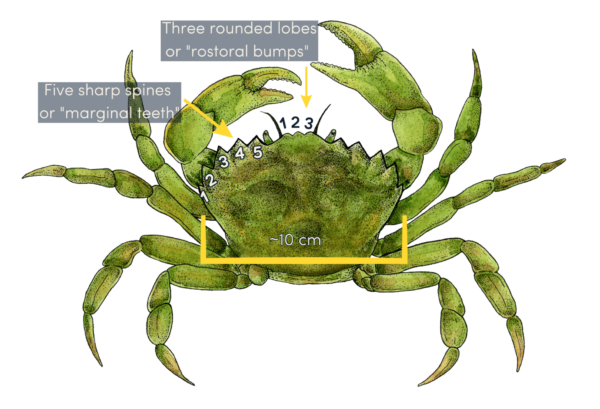

Despite the name, EGCs are not always green! They can be identified by three rostoral bumps and five marginal teeth. (Anisha Parekh)

DFO staff initially trained PSF and CRS on green crab monitoring and identification to expand capacity for detection and removal work. Now, the PSF-CRS team hosts training sessions with First Nations and stewardship groups to build their own capacity in early detection monitoring. PSF and CRS aim to continue strengthening partnerships with communities and mitigate EGC populations across Vancouver Island, and ultimately limit the ecological and socio-economic impacts on coastal ecosystems.

This project is funded by a three-year $700,000 grant from DFO’s Aquatic Invasive Species Prevention Fund to train coastal communities within the Salish Sea, northern portions of the South Coast, and the Central and North Coasts of B.C. to identify these invasive species.