First-of-its-kind winter ecology study provides important clues to salmon mystery

The salmon migration doesn’t stop for cold weather, nor do frigid waters deter researchers from learning about the winter life cycle.

From the northern reaches of the Broughton Archipelago to the southern tip of Vancouver Island, Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) scientists work with partners throughout the winter in their quest to learn more about salmon.

Although the first winter that salmon spend in the ocean is thought to play a critical role in their overall survival, surprisingly little is known about this period. This is in no small part due to the challenges of conducting ocean research in winter weather.

Thanks to a collaboration launched in 2020 by PSF and British Columbia Conservation Foundation (BCCF) and supported by the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund (BCSRIF), the Bottlenecks to Survival program investigates when and where Chinook, coho, and steelhead face critical mortality periods or “bottlenecks” during the freshwater and early marine periods of life.

The Bottlenecks program focuses on factors that may lead to declines in salmon populations including predation, competition, and climate change. The research team focuses primarily on the East Coast of Vancouver Island.

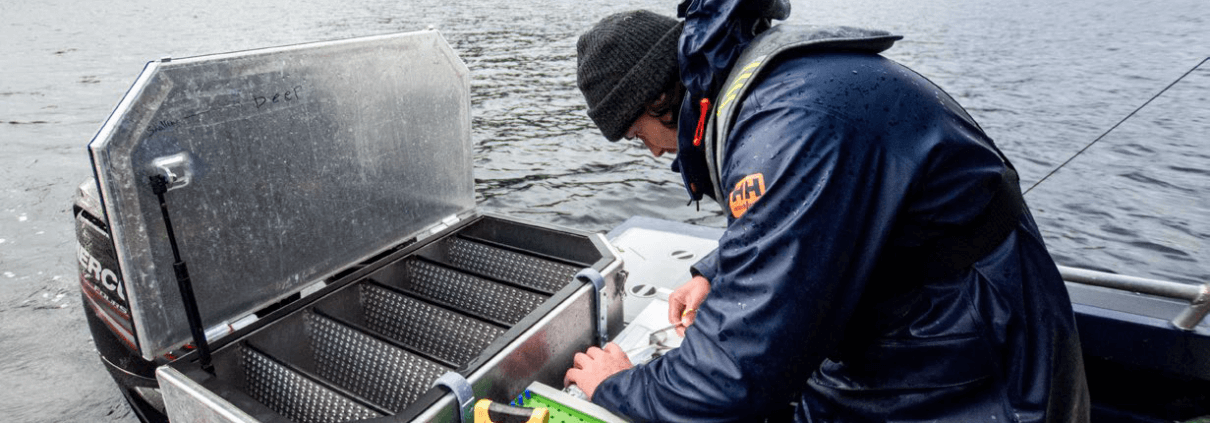

(Nick Bohlender)

Supervised by Isobel Pearsall at PSF and Jamieson Atkinson at BCCF, the Bottlenecks team collects first-of-its-kind data on juvenile Chinook salmon winter habitat, diet, and health in the Salish Sea.

“As many populations of wild Chinook, coho, and steelhead have experienced steep declines in the Salish Sea, and considering their importance, it is urgent that we increase our understanding of the factors and mechanisms that may contribute to their reduced numbers,” says Pearsall.

Under Pearsall’s leadership, PSF’s Bottlenecks program activities are managed by post-doctoral fellow Will Duguid of the University of Victoria (UVic).

“At its core the Bottlenecks program seeks to identify if and when there are critical mortality periods in the life of Chinook and coho salmon and steelhead. Understanding if and when such periods occur can help managers and those who fish understand how different strategies can be employed to aid in salmon recovery,” says Duguid. “In addition to understanding when critical mortality occurs, we also conduct complementary studies to understand how death may occur, for example by predation, starvation, or fishing”

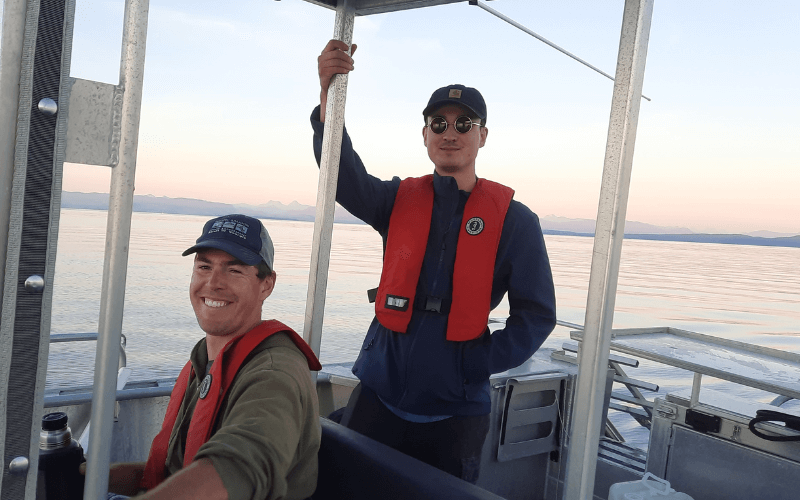

Will Duguid and Jake Dingwall.

Winter field work: Microtrolling and volunteer anglers

The research team uses data collected by Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags to help answer the first of these questions. About the size of a grain of rice, the tags provide a unique identification code — similar to the way the ‘tap’ feature works on a bank card — when their host fish encounters an antenna. The tags track individual fish survival back to the river and enable a comparison of survival of fish tagged at different life-history stages.

A life-long angler, Duguid developed an economical way to nonlethally sample and tag juvenile Pacific salmon called “microtrolling.” (Watch a quick video here.)

His method repurposes recreational fishing gear and small boats in a unique way, so that juvenile salmon are not harmed.

“Our small-boat approach makes science accessible to First Nations, community groups, and non-profits that may not have access to big-ship work. Our method of sampling and tagging has been picked up by others,” says Duguid.

Duguid works closely with BCCF’s Jamieson Atkinson, fisheries biologist and co-manager of the Bottlenecks program. Atkinson oversees volunteer anglers — citizen scientists who use their own boats to collect data.

During 2022, Atkinson noted that the team had outstanding catches — 40 to 50 per day — in the winter in the Discovery Islands area, and stocks that were sampled were determined to be predominantly from the Quinsam, Puntledge, and the Big and Little Qualicum rivers.

This year—not so much.

“The migrations and movements of Chinook this year were about a month later when compared to previous years due to the cold spring. We have yet to observe those similar catches as last year, but we are still hoping the fish will show up and that they’re just delayed.”

Atkinson notes that it’s too early to speculate on why catches have changed, considering the first few years of the study have had extraordinary anomalies like Covid reducing the number of sea-going vessels, a heat dome, atmospheric river, late freshet, and extensive drought.

“Considering all these outliers, we need at least 10 years of data to show a clear picture,” says Atkinson.

Winter ecology: Diet, growth and disease

Researchers Will Duguid and Katie Innes. (Nick Bohlender)

While PIT tagging can tell us if winter is a critical period for survival, additional sampling is needed to answer questions about why it might be a critical period.

Duguid supervises a team of graduate students within Professor Francis Juanes’s laboratory at UVic. He and his team are supported by PSF-Mitacs funds that leverage Canadian federal and provincial resources to advance innovation.

Master’s student Katie Innes has been working with Duguid on the winter ecology research since 2020. Her work focuses on the overwinter feeding and energy budget of juvenile Chinook in the Strait of Georgia. She studies their diet, physical condition, and first-year growth, and how these factors may influence survival rate.

“The first year of Pacific salmon life is a black box. We don’t know what they’re eating from October through March,” says Innes. “We’re studying how the energy content of their prey relates to salmon health.”

Using a non-lethal sampling method that includes flushing their stomach contents, Innes is able to learn exactly what first-year salmon eat. And she’s had some interesting findings.

“Sometimes the prey is still alive. We’ve found Northern Anchovy, tiny sea stars, crabs, crab larvae, krill, and octopus. We’ve found squid with their tentacles still moving.”

Innes explains that energy-dense (high calorie) foods are best for salmon to eat to grow big during their first year, and both fish and zooplankton prey are important.

She notes that juvenile Chinook seem to be growing up until about December, and then the research shows rapid declines. However, the reasons behind the reduced growth in the early new year are not yet clear.

Innes is modelling fish sizes throughout the first-year period. Her model includes Chinook energy and prey energy, water temperature to sea floor, and fish growth and consumption.

“Getting out on the water in winter can be challenging. You can only fish on a small boat when the weather is nice. For most of the winter, we are ‘on call’ waiting for a window of calm seas,” says Innes.

Hear hear: Acoustic tagging in the winter

Wesley Greentree, a UVic colleague, works with the Bottlenecks program studying salmon ecology and migration behaviour using acoustic tags.

From October through January, Greentree places small electronic “acoustic” tags in the body of first-year Chinook in the northern Strait of Georgia near Comox. The tags produce a series of high-frequency pings that encode a unique identifier. The sounds are detected by hydrophones, which decode the pings into the unique identifier which allows the research team to know when a tagged fish swims past a certain location.

“Our goal is to use acoustic tags to track salmon as they move within and out of the Salish Sea,” says Greentree.

Some Chinook Salmon stay resident in the Salish Sea for most or all of their marine life.

“We want to determine if resident Chinook differ from Chinook that migrate out of the Salish Sea, and if so, how. For example, do residents and migrants differ in body size, early marine growth or pathogens? And if so, does this affect their survival?”

The second goal of this project is to determine when Chinook salmon migrate out of the Salish Sea. Greentree looks forward to exploring this important piece of the puzzle next.

“I grew up in Campbell River so it is exciting to be on the water the entire winter, and to work on salmon so close to home,” says Greentree.

Bottleneck collaborators

The Bottlenecks to Survival program is broad and highly collaborative in nature, with key project partners including DFO’s Salmonid Enhancement (SEP) and Stock Assessment Division (StAD), the Provincial Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations (FLNRO), and the University of Victoria (UVic).

Partners also include a number of community groups, non-profit stewardship organizations, and First Nations — whose traditional lands and rivers the Bottlenecks team works in to carry out field research.

Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia also partner in data collection and field sampling and provide on-the-ground support. The majority of the marine sampling is carried out by volunteer anglers and citizen scientists throughout the Salish Sea region.

Much of the data and maps from this project are publicly available at the Strait of Georgia Data Centre.