Warm water temperatures in the Fraser and Columbia pose risk to sockeye returns

By Jason Hwang, Chief Program Officer and Vice President of Salmon, Pacific Salmon Foundation.

August 15, 2024

Water temperatures in the mighty salmon-bearing Fraser River and the transboundary Columbia River have exceeded the tolerable threshold for Pacific salmon this summer, leading to concerns for sockeye that are currently migrating back to spawn.

Climate scientists forecast that warm temperatures and other watershed impacts like low flows will occur more frequently due to climate change.

In the face of these conditions, Pacific salmon need long-term solutions and coordinated management prioritizing salmon recovery and resilience.

In-season warm waters

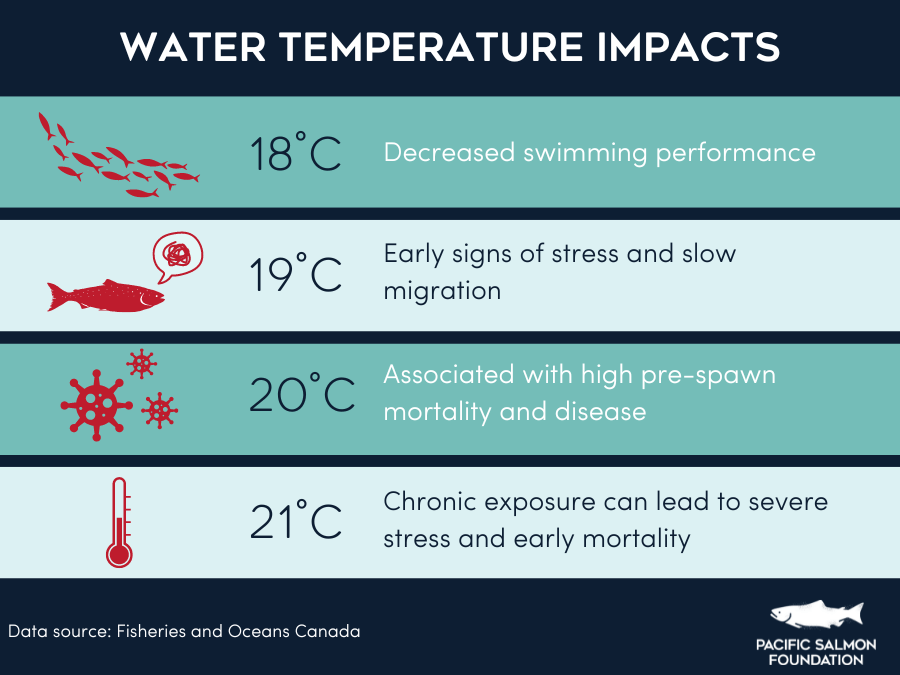

Water temperatures above 18°C can lead to decreased swimming performance, stress, pre-spawn mortality, and disease in Pacific salmon.

Water temperatures in the Fraser River are currently as high as 21°C, and have consistently been above 18°C since mid-July. At these high temperatures, mortality en route to spawning habitat becomes a tangible risk for migrating salmon.

Amid these above-average water temperatures, the outlook for Fraser sockeye has been disheartening. The first run, the “early Stuart” group that return to the Takla Lake area, was expected to be low this year due to impacts from the 2019 Big Bar Landslide that blocked the parent year for this population from making it to their spawning grounds in 2020. Only a small number (less than 50) of early Stuart sockeye have been observed on the spawning grounds as of early August. In a typical year, most of these fish would have returned by now.

The return will likely be extremely low this year this year for this very important population of Fraser sockeye. While returns for this population have natural highs and lows, the return was approximately 800,000 sockeye in the mid-1990s. In 2020, only 30 early Stuart sockeye were estimated on the spawning grounds (98 per cent below target), despite hundreds of fish that were collected for broodstock as part of a broader conservation enhancement initiative. There was hope that these conservation enhancement efforts would help augment this population and mitigate impacts from the Big Bar Landslide, but these efforts may not be as beneficial as hoped.

More broadly, the total return forecast for Fraser sockeye is approximately 560,000 for the year. While this is not the lowest projection on record, it is relatively low.

Conversely, this year a record-high sockeye run on the Columbia River is projected. More than 750,000 sockeye are returning in the Columbia River system, a remarkable increase from recent years. The improved returns over the last 15 years are a result of collaborative efforts, improved management, and habitat rehabilitation efforts on both sides of the border. The Okanagan Nation Alliance have been instrumental in leading a long-term salmon recovery strategy. Their sockeye success story is a hopeful example demonstrating the potential of salmon recovery.

Despite the strong sockeye return in the Columbia, the watershed also struggles with warming waters.

High river temperatures are causing sockeye to hold south of the Canadian-U.S. border, delaying their migration into the upper stretches of the river which could negatively affect the number of salmon that are able to successfully spawn. Salmon rely on cool temperatures, rain, or flushing events to trigger their migration. Without these triggers, salmon will wait. Sockeye are a relatively small salmon species, so they have less capacity for holding and are more vulnerable to warm temperatures.

What we can do

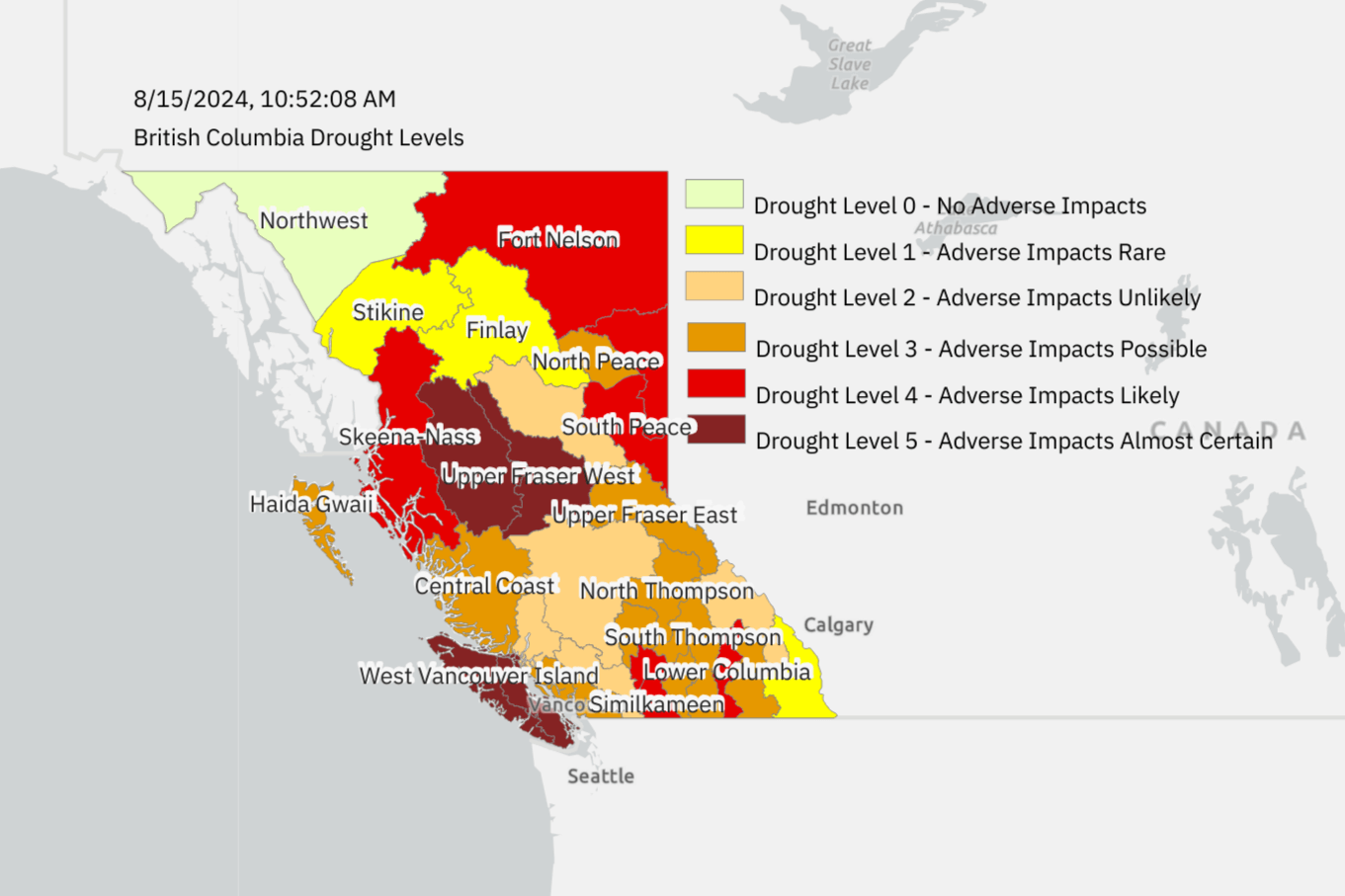

British Columbia has now faced extreme drought conditions for four consecutive years. As of August 15, 39 per cent of the province is experiencing level four of five drought, the most severe categories. And the drought season is far from over.

Source: B.C. Drought Information Portal

Drastic conditions, like the warm waters this season, will occur more frequently in our changing climate. We know these impacts are coming, so we must anticipate them and proactively protect watersheds and Pacific salmon.

Waiting idly for these conditions to unfold is not an option because once they start happening in real time, little can be done to improve the situation.

Instead, we can look to long-term planning, investments, and restoration efforts.

We need to prioritize investments that increase watershed recovery and resilience. Some examples include large-scale re-planting riparian vegetation to restore shading around streams where surrounding trees have been lost to wildfires or industrial activities, improving water management to ensure water is available when flows are low, and using restoration techniques like beaver dam analogues to restore healthy pond and floodplain habitat, which can mitigate impacts from drought conditions.

We also also need robust plans in place for salmon recovery and long-term sustainability and resilience. These should include appropriate conservation-focused fishery management and consideration of conservation enhancement to create new tools in our toolkit when extreme events occur.

It is important to recognize that there is no single cause of problems for salmon and no simple solution. However, it is possible to make notable improvements if we coordinate our work under a thoughtful strategy and implement appropriate measures.

Long-term and collaborative landscape and watershed resilience measures will help us prepare for and adapt to climate change events and allow us to best support Pacific salmon and their habitats through substantive solutions and lasting funding.

Salmon are resilient, and there is a hopeful future, but we need to take bold and decisive action to help change the course for populations that need our help.