Exceptionally warm ocean conditions are impacting BC marine life.

By Ian Perry, (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Pacific Biological Station and Peter Chandler, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Ocean Sciences

The warm and dry weather that British Columbia has experienced this spring and summer is due in part to exceptionally warm ocean conditions.

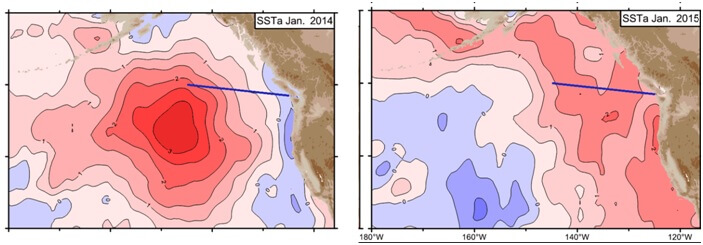

Typically atmospheric patterns over the Pacific Ocean generate winter storms that cool the surface layer by mixing it with deeper water. In the fall of 2013, atmospheric conditions deflected the strong winter storms northwards into Alaska and the Canadian far north. In the absence of these storms the surface waters in the NE Pacific got warmer and warmer, so that by the spring of 2014 water temperatures were more than 3 °C above normal in an area larger than British Columbia and Alberta combined. Such warm conditions have not been seen in this region since open-ocean temperature record keeping in the NE Pacific began in 1948.

In the fall of 2014, the winds from the west resumed and blew this warm surface water to the coast of North America causing record high sea surface water temperatures during the winter of 2014 and the spring of 2015. These ocean conditions warmed the atmosphere and helped to create the dry weather conditions that British Columbia has experienced for the past several months.

These warm ocean conditions have also affected the marine ecosystem by changing the distributions and migrations of many species of fish, bringing predatory fish to British Columbia which are normally found off California, and changing the type of zooplankton at the base of the food web.

The species of zooplankton that typically live in the cool waters off the coast of British Columbia provide a nutritious food source for fish. The warmer waters are now bringing to the coast zooplankton typically seen off California that are smaller and less nutritious than their BC counterparts The displacement of the BC zooplankton means that fish like salmon will have to work harder for their meals.

Zooplankton like moon jellys are primarily made of water and less nutritious than other species.

The consequences of these ecosystem changes – more predators, poorer fish food – are that juvenile salmon entering the ocean in 2015 have experienced an environment much different from normal, which is likely to affect their growth and survival.

Along with more predatory fish, the warm water has brought northwards species which are rarely seen in BC waters, such as the Pacific Pompano (also known as butterfish), and species which have never been seen in British Columbia, such as the Finescale Triggerfish (Balistes polylepis; see http://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/staffprofiles/2015/04/02/warm-water-triggers-new-fish-records).

Warm water has brought northwards species which are rarely seen in BC waters, such as the Pacific Pompano (also known as butterfish).

Sockeye salmon returning to spawn in the Fraser River pass by Vancouver Island via the northern route through Johnstone Strait or the southern route through the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Warm water conditions, such as those as experienced this past year and during El Niño events, tend to favour the return of the Sockeye via the northern route. In 2014 an estimated 96% of the returning Fraser River sockeye salmon travelled through Johnstone Strait.

The Climate Prediction Centre in the United States has advised there is a 90% probability that El Niño conditions will occur until 2016.This will bring additional warm water to British Columbia from the south. Such strong El Niño events typically cause warm and dry conditions in British Columbia. Environment Canada has forecast a 90% chance of above normal air temperatures, and a greater than 40% chance of below normal rainfall, at least until the end of September 2015.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to monitor ocean conditions off British Columbia to determine if these warm water conditions are part of a cycle, represent a long-term trend, or are a one-time event.

This figure shows changes of surface water temperature from normal in the NE Pacific, in January 2014 (left) and January 2015 (right). The very warm water (dark red patch, over 3 °C above normal) moved to the coast of British Columbia by January 2015, causing record high water temperatures at some locations. The blue line represents locations monitored by Fisheries and Oceans Canada since 1948. Figure courtesy of Howard Freeland, based on data available from the United State National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.