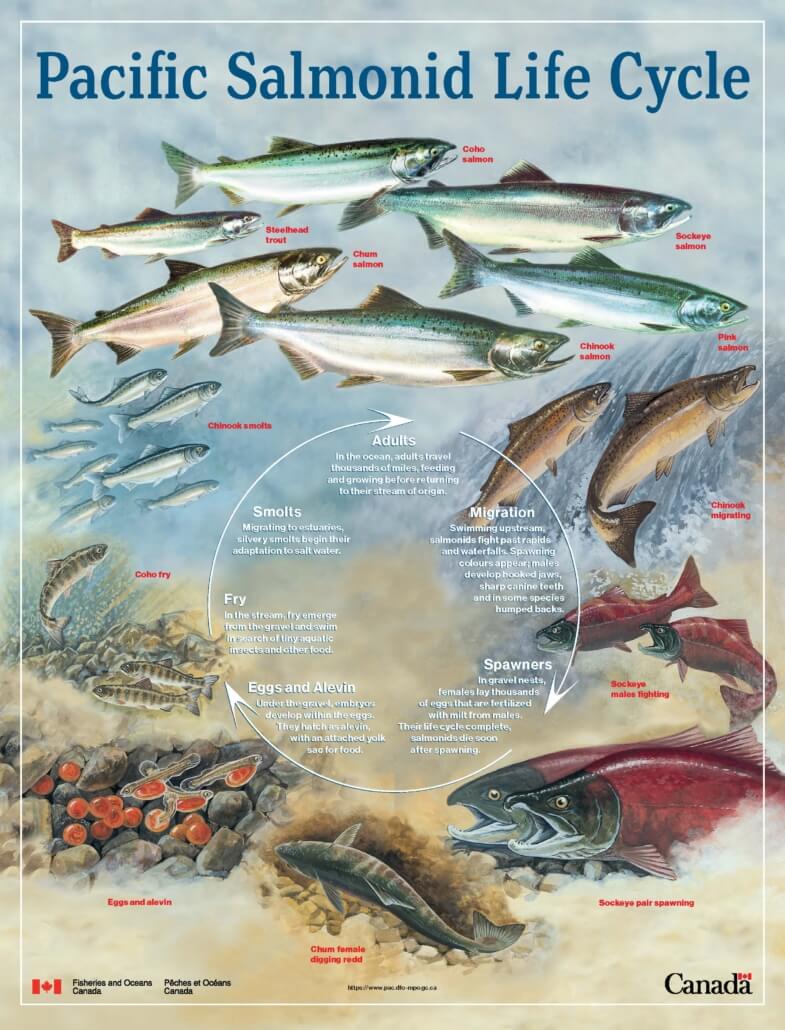

The Pacific salmon life cycle depends on the species. Some spend hardly any time in natal streams; some spend years. Some mature at two years of age; some mature at five. Some live for only a couple of years; others live for ten. And some, like Steelhead and Cutthroat, can spawn more than once.

Despite these variations, we can still make some general observations about the life stages of salmon.

All Pacific salmon are anadromous, which means they start in freshwater (streams, lakes, rivers, etc.), migrate to the ocean, then return home to spawn and die.

Species and Lifecycle information and images contributed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

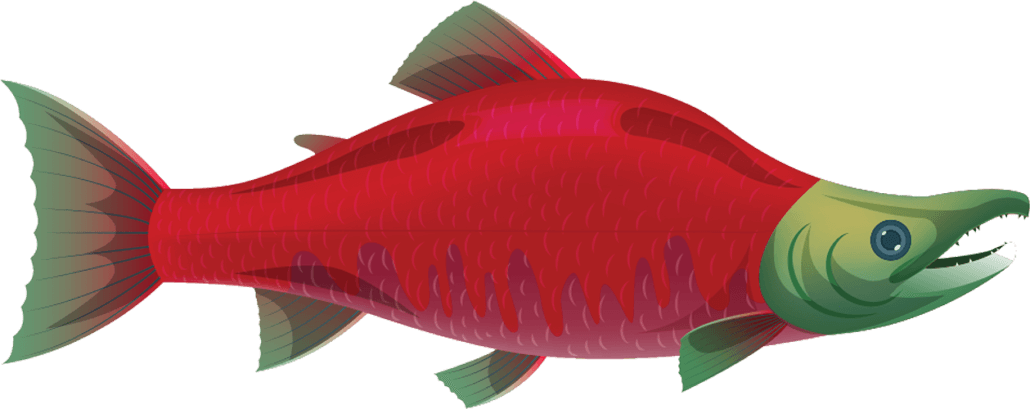

Adult spawners often journey for hundreds of miles to return to the waters their parents spawned in, and where they themselves were born.

If they make it back, evading all sorts of obstacles—predation, competition, environmental impediments, the males and females court, and ultimately breed. At the crucial moment, the male releases sperm and the female releases eggs… at precisely the same time!

The eggs and sperm float in a fog of milt to the bottom of the stream or lake bed where the female has painstakingly prepared a redd (aka nest), which, covered with gravel, is expected to protect the eggs until they are ready to hatch.

While new salmon are preparing to enter the world, their parents die (usually only days after spawning). Their bodies remain in the water or along the shore to decay and/or be eaten by other species. In this way they continue to nourish the environment around them.

Egg

Some of the thousands of eggs that the female has released will be successfully fertilized by the male’s sperm. Salmon eggs are very fragile and many are destroyed, underscoring the importance of habitat protection in conserving salmon stocks.

Inside the egg is an embryo and a yolk which feeds it. For a while, the embryo has enough oxygen inside the egg, but as it grows, it needs more. Finally it reaches the breaking point and struggles free of its egg shell, though not yet discarding its yolk. It is now an alevin.

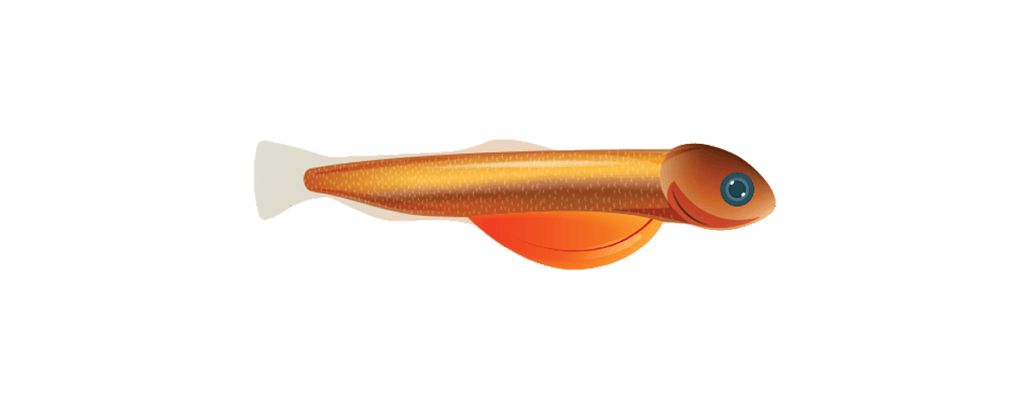

Alevin

Alevin’s yolk sac contains sufficient nutrition for their early development. They remain under the gravel for protection against predators until their yolk sac is fully absorbed. It is virtually impossible to see alevin in the wild.

Salmon fry are vulnerable to predation as they develop into fry.

Fry

Once it has absorbed its yolk, the alevin becomes a fry. Small and vulnerable, fry spend a lot of their time avoiding predators. They head for dark pools in protected spots (e.g., behind logs) and dart out only to catch and eat any organic matter that comes their way. When they feel the urge, they begin their migration toward the ocean (see Species for the different migratory patterns that characterize each species).

Smolts

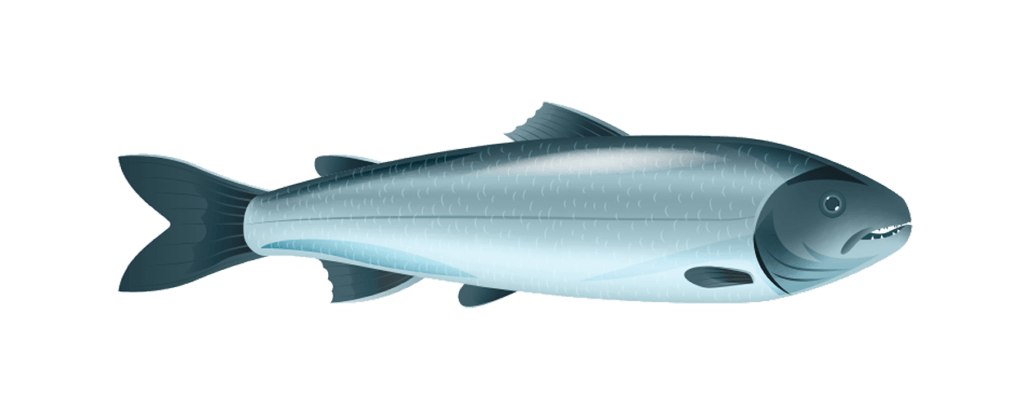

To manage the transition between freshwater and saltwater, salmon fry must go through a physical change known as smolting. Smolting begins in freshwater and sees the young salmon through the estuaries and into the ocean when it is time. Smolts have a silvery coating over their scales to camouflage them from predators and shield their bodies from fresh to saltwater.

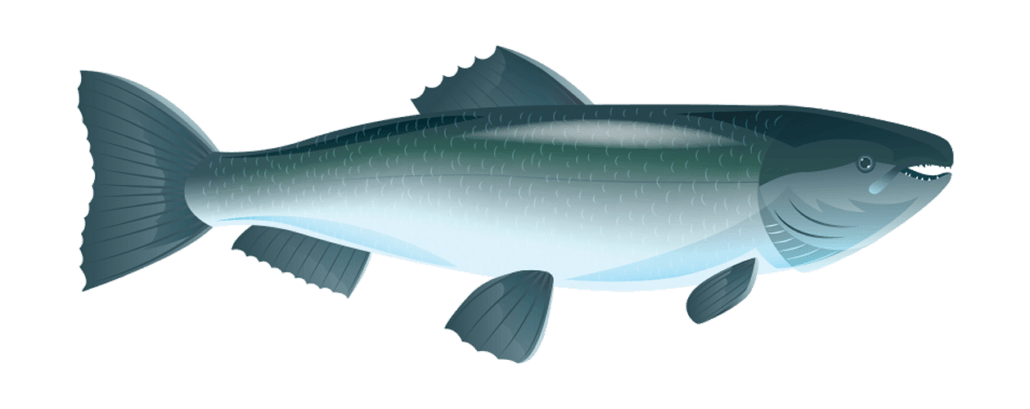

Juvenile Adults

Salmon enter the ocean as young, or juvenile, adults and leave it as mature adults, ready to spawn. The length of time salmon spend in saltwater depends on how old they were when they entered, their species, marine conditions, and other factors. Their travels in the ocean are similarly variable, and one of the least understood parts of their lives.

Breeding Adults

When they are sexually mature, salmon follow their homing instinct and travel back to their natal streams to spawn. It is an arduous journey, and only the toughest and luckiest salmon complete it.