Central Coast: Salmon in Crisis

Jennifer Walkus has been concerned about the collapse of salmon on the Central Coast of B.C. since the 1970s.

Both her father and grandfather worked in salmon management. Her father was the fisheries manager for Wuikinuxv Nation and her grandfather was a creekwalker employed to count salmon with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). As a child, Walkus closely shadowed her father and quickly picked up his interest in resource management. Like her grandfather, her father often led creek walks in their territory. By the ’70s, he noted alarming salmon declines.

Walkus herself embarked on a career to protect salmon, starting as a fisheries assistant for the Wuikinuxv Nation in the 1990s, then later taking on roles as fisheries manager and stewardship director. Now, as an elected councillor for Wuikinuxv Nation, she laments the declining state of salmon.

“We’re losing out on a lot of our culture because we don’t have the salmon populations to support our needs anymore,” says Walkus.

The Walkus family is from Wuikinuxv Nation, a community that has relied on millions of salmon returning to the rivers and streams in their territories for millennia. As with many Indigenous communities in B.C., Wuikinuxv culture and survival are connected to salmon — a resource that has provided food security and economic stability for the community.

Dramatic declines in salmon populations in recent decades have changed everything. The abundance of salmon returning to Wuikinuxv territory is only a fraction of what it once was. Owikeno Lake sockeye, for instance, historically recorded annual returns in the range of two to six million fish. Today, the returns have plummeted to 200,000. Populations have declined so drastically that in four of the last five years, the Nation has closed its own sockeye food fishery, which was once one of the most impressive runs on the coast. “We take the health of our ecosystem seriously,” says Walkus.

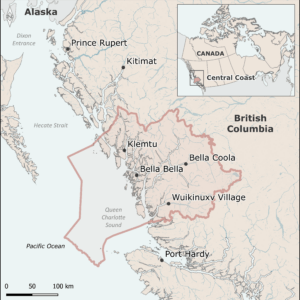

The Wuikinuxv’s salmon circumstances resemble trends occurring across the entire Central Coast of B.C. The traditional territories of the Heiltsuk, Kitasoo Xai’xais, Nuxalk, and Wuikinuxv First Nations cover more than 55,000 kilometres of terrestrial and marine ecosystems on the Central Coast, including some of the province’s most intact and productive salmon habitats.

Abundant wild salmon on the Central Coast have been essential to the culture and prosperity of First Nations for more than 10,000 years. Today, most salmon populations are not what they used to be.

In recent years, climate change, overfishing, and habitat destruction have transformed conditions for salmon, leading to the collapse of a once-thriving salmon ecosystem. Salmon returns to the Central Coast have reached historic lows. Furthermore, due to data deficiencies as a result of reductions in monitoring efforts over the past decade, the full extent of salmon declines remains unknown.

Kitasoo Xai’xais research technician Ben Edgar samples sockeye salmon for DNA collection. (Tavish Campbell)

Since 2016, PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program has worked with Central Coast First Nations and the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance (CCIRA) to improve access to baseline data and develop tools to assess the state of Pacific salmon and their habitats in the region.

This work has involved numerous steps, including:

- Data compilation and salmon status assessments

- Characterizing major threats to salmon and prioritizing strategies for supporting their persistence

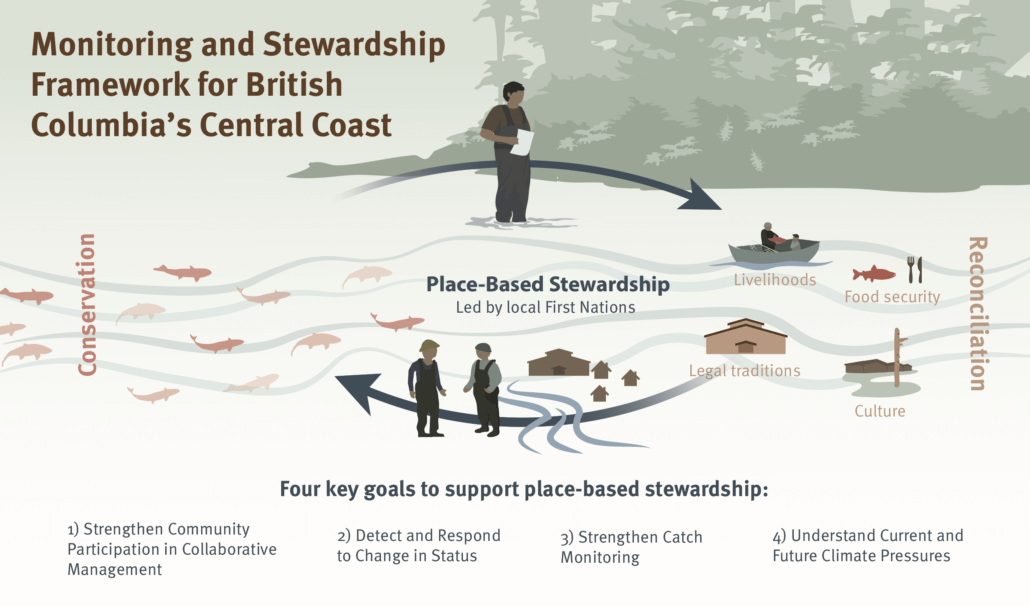

- Developing an Indigenous-led salmon monitoring and stewardship framework

- Strengthening Indigenous-led escapement monitoring efforts

Status assessments confirm low returns

Leah Honka (PSF), Eileen Jones (PSF), Lena Collins (Wuikinuxv Guardian Watchmen).

The collaboration began with developing a publicly available baseline of information on the status of salmon and their habitats. Much of the data that had been collected for Central Coast salmon were scattered in a number of different databases and were difficult to access. PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program worked with local salmon experts to identify the best available data sets and bring them together in a centralized database. This data were used to undertake assessments of the current state of salmon and their freshwater habitats and made available in the Pacific Salmon Explorer, an online data visualization tool for B.C. salmon developed by PSF.

These analyses have shown that many Central Coast sockeye runs have declined by more than 74 per cent since 2005 with chum down 43 per cent.

But the data aren’t perfect.

Recent efforts to assess the status of salmon and their habitats in the region have revealed major data gaps, due in part to declines in funding to support monitoring efforts over the past decade. In fact, the biological status of more than 50 per cent of all salmon on the Central Coast could not be assessed due to a lack of baseline salmon stock assessment data. Since 2006, the number of routinely monitored spawning streams on B.C.’s North and Central Coast has declined by half creating more unknowns regarding the state of salmon in the region.

Despite the gaps in data, community members have observed significant changes in local salmon populations for many years.

“We’re seeing real climate change impacts in front of our eyes. It hits home really hard,” says Vernon Brown, outdoors coordinator and field technician for the Kitasoo Xai’xais Stewardship Authority. “Last year was a scary year with low coho numbers. It wasn’t the first time we’ve seen numbers that low, but it was kind of an awakening for the coast.”

Brown, who has been doing creek walks for eight years and previously worked in eco-tourism, says he’s been growing an understanding of how salmon are faring.

“This collaborative work gets us closer to being proactive rather than reactive in our fisheries management,” he says. “Salmon data collection and quality is super important to my community. We can use that and make on-the-fly fisheries decisions to protect what’s left.”

200+ conservation recommendations

The initial data synthesis and status assessments indicate there are opportunities for greater coordination, standardization, and investments in salmon monitoring.

More recently, several Central Coast First Nations, PSF, and CCIRA teamed up with DFO and regional salmon experts to develop and work towards implementing a regional Salmon Monitoring and Stewardship Framework for the Central Coast (the Monitoring Framework). The Monitoring Framework identifies shared goals for salmon conservation and management, and prioritizes strategies and actions for collaboratively working towards these goals.

“Central Coast First Nations are working to develop capacity to manage their marine resources informed by work such as the Monitoring Framework,” says Rich Chapple, president of CCIRA. “This framework will serve as a structured guide for strengthening the scientific foundations for fisheries governance approaches that support conservation and recovery efforts for wild Pacific salmon and the communities who depend upon them.”

More than 200 actions have been identified for helping to realize these goals. One of these actions calls for improvements in salmon escapement monitoring and expanding upon the kind of creek walks that Walkus’ father and grandfather led years ago.

Improving monitoring efforts

Jason Moody (Nuxalk Fisheries and Wildlife Office) and Kate McGivney (Wild Salmon Centre) sample sockeye

at Atnarko River. (Julian Heavyside)

Today, much monitoring effort is focused on “indicator streams,” which provide a good indication of the state of salmon populations within a given area. While these streams are important to monitor, they are not inclusive of all salmon streams that are valuable to the Central Coast First Nations — for example, streams that support food fisheries and tourism.

To address this, the project collaborators worked to identify priority streams for escapement monitoring as identified by each of the Central Coast First Nations. This included developing an online interactive Escapement Monitoring Tool for visualizing these priority streams and ultimately supporting the Nations in planning their escapement monitoring activities in their territories.

“The Central Coast Escapement Tool redefines how monitoring priorities are identified. Instead of focusing our efforts on monitoring salmon populations that are important to commercial fisheries, we worked with the Central Coast Nations to identify those populations that are central to their cultures, economies, and food security to ensure that monitoring efforts are directed to populations of local importance,” says Dr. Katrina Connors, Director of PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program.

Teddy Windsor of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department’s

Coastal Guardian Watchmen counting salmon in the Upper Kunsoot River. (Olivia Leigh Nowak)

The development of the Salmon Monitoring and Stewardship Framework and support for advancing its implementation has been provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts. CCIRA and the Central Coast Nations have also secured grants from the B.C. Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund to support the implementation of the Monitoring Framework including developing a recreational catch monitoring program and identifying priority watersheds and implementing activities aimed at restoring wild salmon. Over the next two years, Central Coast Nations will be investing in Indigenous-led restoration efforts further helping to improve community capacity for salmon monitoring and stewardship.

“This project exemplifies how collaborative conservation planning can support community empowerment and the fulfillment of local objectives focused on sustaining the resilience of wild Pacific salmon,” says Dr. Connors.

Amy Romer

Amy Romer